This 3,750-Year-Old Babylonian Tablet Is the World’s Oldest Recorded Customer Complaint

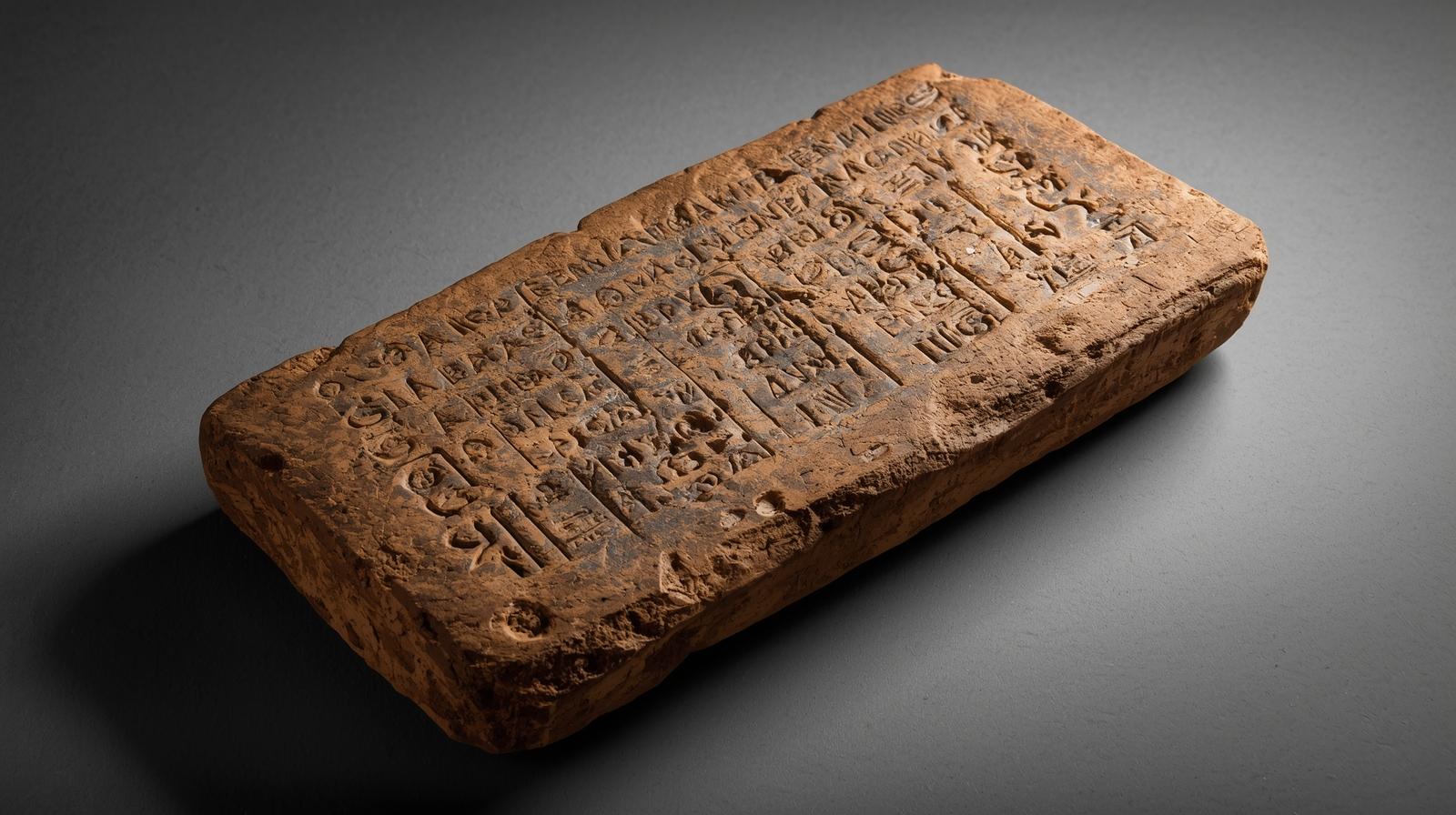

In the British Museum in London lies a unique artifact that offers a glimpse into the daily lives and frustrations of people who lived nearly four millennia ago. The 3,766-year-old clay tablet, originating from the ancient Mesopotamian city-state of Ur, is widely recognized as the world’s oldest known recorded customer complaint. Its existence is a fascinating reminder that even thousands of years ago, people knew the frustrations of poor service and unmet expectations.

A Window Into Ancient Commerce

The clay tablet dates back to around 1750 BCE, during the reign of the Babylonian Empire. Ur, located in what is now southern Iraq, was a major hub of commerce, trade, and administration. Merchants, craftsmen, and ordinary citizens relied on precise business practices and trustworthy delivery of goods—just like today.

Unlike most ancient documents, this tablet is not a legal decree, royal edict, or religious text. Instead, it is a personal note from an individual expressing frustration with a supplier. The text shows that disputes over trade and delivery have existed for thousands of years, proving that complaining about bad service is far from a modern phenomenon.

The message, written in cuneiform, the wedge-shaped script used throughout Mesopotamia, was inscribed on a small clay tablet designed to be durable. In the tablet, the complainant explicitly requests a replacement for goods that were not delivered as promised. This early example of customer dissatisfaction is astonishing not just for its age, but for its remarkable similarity to complaints that might be submitted to a business today.

The Story Behind the Discovery

The tablet was unearthed during excavations at Ur, a city whose ruins have provided archaeologists with some of the richest insights into early urban life. The site gained international attention largely due to the work of Sir Leonard Woolley, a British archaeologist who began systematic excavations in the 1920s and 1930s.

Woolley’s research at Ur was meticulous. He documented everything from royal tombs to ordinary domestic spaces, offering an unprecedented look into Mesopotamian civilization. It was through these excavations that the tablet containing the complaint was recovered. Woolley and his team carefully cataloged thousands of cuneiform tablets, revealing the social, economic, and administrative complexity of Ur. Among these discoveries, the “complaint tablet” stood out because it captured personal voice and human emotion, rather than bureaucratic or religious formalities.

What the Tablet Says

The tablet’s text is brief but expressive. The complaint concerns a shipment of copper ingots that were either missing or delivered in poor condition. The inscriber demanded that the responsible merchant, a man named Ea-nasir, deliver a replacement. The text also contains a sharp rebuke for the merchant’s failure to uphold his promises, reflecting both frustration and the expectation of accountability.

- Translated loosely, the complaint reads something like this:

“I received the goods you sent, but they were not of the quality I ordered. I repeatedly sent messages requesting proper delivery, but you did not listen. Why do you treat me with contempt? Send the correct goods at once.”

It is remarkable that over 3,700 years ago, customers demanded quality service, accountability, and fairness—principles that continue to shape commerce today.

Insights Into Babylonian Trade

The tablet not only documents human dissatisfaction but also provides scholars with valuable information about Babylonian commerce and social norms. It shows that trade involved complex logistics, standardized measurements, and the expectation of accurate fulfillment.

Babylonian merchants like Ea-nasir operated in a system that demanded reliability and trust. Cuneiform tablets often served as contracts, receipts, or complaints, demonstrating that economic transactions were formalized and recorded for accountability. For historians, such tablets shed light on:

- The social hierarchy of Ur: Who could send complaints and who was expected to respond.

- Ancient supply chains: The movement of copper, grain, and other essential goods.

- Legal and economic practices: How disputes were formally documented and resolved.

Even though the complaint is simple, it reveals a sophisticated understanding of business ethics, showing that merchants were held responsible for failing to meet expectations.

Sir Leonard Woolley: Archaeology’s Iconic Figure

The discovery of the tablet is inseparable from the life and work of Sir Leonard Woolley, who is widely regarded as a pivotal figure in modern archaeology. Born in 1880, Woolley developed meticulous excavation techniques that combined scientific rigor with careful documentation of artifacts.

At Ur, he uncovered the famous Royal Tombs, along with thousands of domestic and administrative objects. His work created a detailed picture of Mesopotamian civilization, including its architecture, art, religious practices, and everyday life. The complaint tablet is just one example of the kind of mundane yet historically significant items that Woolley brought to light.

By studying artifacts like this tablet, Woolley helped establish that ordinary people in ancient societies had voices, opinions, and rights, even in matters as mundane as receiving faulty goods.

Why This Tablet Matters Today

What makes this tablet extraordinary is its humanity. Across the centuries, it reminds us that people in the ancient world experienced similar frustrations, desires, and expectations as we do today. Some of the key takeaways include:

- Customer complaints are timeless: Humans have always demanded fair treatment and accountability.

- Commerce required trust: Even in 1750 BCE, transactions depended on the reputation and reliability of merchants.

- Historical continuity of human behavior: Emotion and dissatisfaction are constants in human interaction.

- Durability of written records: Clay tablets allowed messages to survive thousands of years, providing modern scholars with insight into daily life.

The tablet also serves as a reminder that history is not only about kings, wars, and grand constructions—it is also about everyday experiences that shaped human society.

The Modern Connection

It is not difficult to imagine a similar scene today: a customer writing an email or leaving a review online about poor service. The tone and intent are strikingly familiar, showing that, despite all technological progress, human expectations remain consistent.

In an era dominated by instant feedback, online reviews, and customer service departments, the Babylonian complaint tablet is a humorous yet humbling illustration that some frustrations are truly eternal.

Conclusion

The 3,766-year-old Babylonian tablet in the British Museum is more than just an artifact—it is a testament to human nature, commerce, and the timeless desire for fairness. From Mesopotamia to modern Britain, it tells a story of frustration, accountability, and the expectation that agreements should be honored.

Sir Leonard Woolley’s excavation at Ur brought this remarkable piece of history to light, bridging the gap between ancient Mesopotamian life and contemporary human experience. It serves as a poignant reminder: no matter the era, good service and accountability have always mattered.

Next time you write a customer review or file a complaint, remember: you are part of a tradition that stretches back nearly 4,000 years. And who knows—millennia from now, someone might be studying your email, marveling at how your dissatisfaction reflects the timeless human spirit.